CINEMA

ARRANGEMENT

Contes et décomptes de la cour – Geography lesson in the harem

The links between aesthetics and knowledge, which will “connect the perception of the social to what is said about it and to the manner in which it is said” [Rancière], involve a formal “dispositif”, or arrangement, that will refract the narrative and bring out the meaning of a reflection. The “dispositif”, in cinema involves the eye and the ear. This notion is always used in the singular, even though it covers a heterogeneous assemblage: scopic or sound materials, formats, colours, sound rendering, limitations of space and time, stage directions, the figure of the actor, ethical values, etc. These elements form a “dispositif”, because, linked together under given conditions, they constitute a creative territory in movement, not a mould. It is the point of view in redeployments and adjustments.

MY CHOICES

→ The Times of Power

During the narration of this first film about a chiefdom in Niger, the royal guards in red turbans gallop to the sound of the Great Royal Drum but go nowhere. I follow these horsemen on horseback. This ‘leitmotif’ device was made on a laterite plateau where I had taken five riders. With this aimless ride, I symbolised both the physical presence of the Samna, who was maintaining his princely heritage, and this tradition, stripped of all content, with guards wearing the colours of the national flag, devoid of any security function and living meagrely off the “royal courier”, in the absence of postmen in the canton.

→ Reflection of life

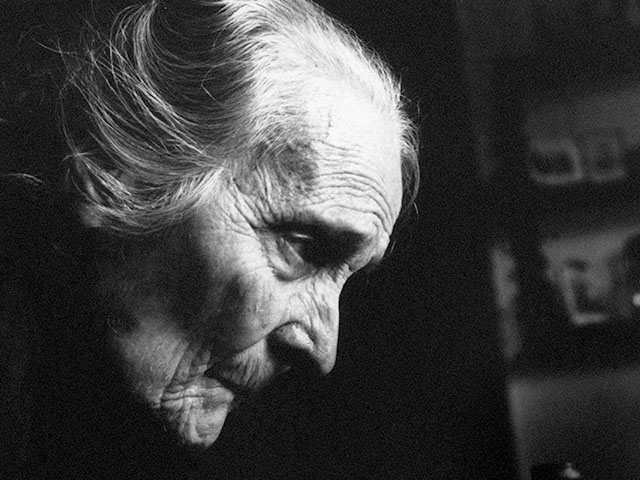

In the middle of this film shot in 16 mm colour, black and white photos appear: this is Hélène, one of the characters in this story about old age. From our first meeting I decided not to use a movie camera. She was very old, with a sculptural face, living tucked away in a deserted hamlet. She walked slowly, dragging her feet, and spoke with dentures that sometimes came loose. A synchronised shot would have made these details realistic and cumbersome. Monochrome, accompanied by her voice-over and a few background sounds, allowed me to honour her inner strength, her great beauty and her silent solitude.

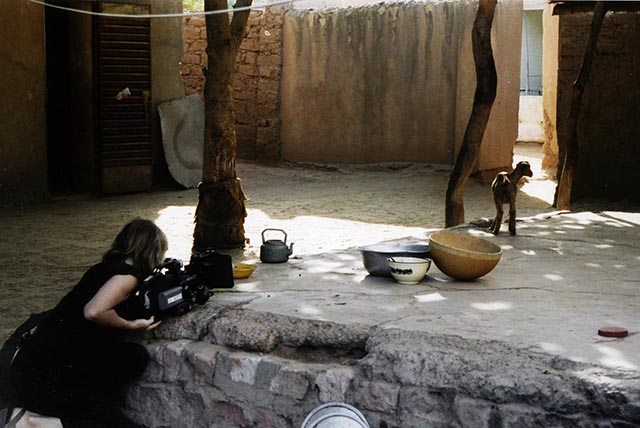

→ Tales and Tallies of the Court

In this harem filmed in Niger, nothing much was happening. You just had to be there to capture the minuscule, the minute events that populated the void, the meaning of which often emerged later. My ears perked up at the complaints about the husband who went to see Hadiza, the 5th wife, whenever he wanted. In this court, Hadiza existed only in the painful evocation of the ‘kichia’: the jealous wives, a term also used to designate ‘co-wives’. This led me to show her only in a de realised mental plane when she is evoked by one of the ‘old women’. We immediately understand something about the pain of confinement, of the impossibility of escape, which is never expressed directly.

→ So Blue, so Calm

In this vast prison, a film camera was used to shoot the communal areas and a still camera was used in the cells. It was a formal decision that was made on the spot. I refused to film a man in his cell synchronously. It would have cannibalised the subjective duration that I was trying to convey. I opted for the artifice of dissociation: individual temporality and prison temporality / questions asked in a collective space and answers written in private / still images and moving images

The decision to introduce dialogue was taken almost as soon as the film was finished. In the first version, I wanted these young “prostitutes” to be recognised without explanation, in the moments of waiting and uncertainty. I chose to film them between waking up late and getting ready to go out hooking; in contrast to the pornographic moments that stigmatise them: fighting, insults, soliciting, outrageous behaviour.

The film was rejected by the CNC and all the festivals, as if a character could no longer be accepted without their Wikipedia entry. Two years later, I had to decide to let the Go speak for themselves. Fortunately, they had changed their lives and could say: “Before, I used to…” For this use of the past tense, I had a small wooden hut built, with a wooden latticework door. A set that created a spatial break with the rest of the film shot in a different context. A way of distancing the blemish.

→ Bronx Barbès

I rejected the idea of shooting directly in the ghettos of Abidjan, which I saw as imbued with a heroin-tinted emptiness that could have produced a form of miserabilism. I was looking for an aesthetic driven by their dreams of transformation on the cutting edge of death. “From endurance to action” [Merleau-Ponty]. This narrative arc required the use of fiction. It also made it possible to legally protect the ghettomen who had become “actors” chosen by open casting. There was a perfect fit between the issues, the investigation, the ethics and the cinematographic expression with these actors, who deserved a tribute to their body language and their imagination.

Making off – Bronx Barbès

TOWARD FICTION

Après l’Océan – Filming ©tomaBaqueni

Throughout my career, I’ve never stopped using fictional processes to highlight the sensitive strata of the social game. In places of relegation where space is scarce and the minute weighs heavily, cinematographic writing is pushed to its limits. “The fiction of a plot can promote what is left unsaid by suspending the referential function of language, which will be revealed through poetry or the imaginative dimension”. [Ricœur]

Go de nuit, forgotten beauties

More than many academic studies, Balzac, Zola, Flaubert, Hugo… have shed light on 19th- century France through “all the powerlessness and all the energies” expressed in the “nonsense of everyday life”. [Émile Zola: 1869]. Similarly, film-maker Kieslowski [2006] declared that he wanted to “enrich the portrait of the human being with an additional dimension, that of feelings, intuitions, dreams, prejudices, in a word, the inner life”, which for the author is not an “underlying and closed world”.

It is a world to which cinema immanently refers.