FIRST STEPS

SAD BEGINNINGS

I arrived on the Black Continent by chance after meeting Marc Piault, an anthropologist, who took me by jeep across the Sahara to his fieldwork sites in Niger. I was drawn by the open sea, and could have gone anywhere. Nothing predestined me for the African continent, or for ethnology. I had just finished studying at the Sorbonne with Georges Balandier and at Sciences Po. It was a period when I was opening up to the world through ideas of Marxist revolution, with Trotskyist and feminist rhetoric that were so out-of-touch that nothing ‘normal’ could come out of it.

I describe this personal journey in a tribute to Françoise Héritier [2018, Herne].

FIRST FIELDWORK SITES

Before I began linking my thesis to politics [Chap. First steps – Thesis], Marc Piault advised me to start with land tenure from a Marxist standpoint: the division of labour and the determination of productive forces. I did so with vain enthusiasm.

With no prior training other than setting up the ineffable field canteen, I set off behind the wheel of a jeep with an interpreter to question as many heads of household as possible about the size of their fields, the number of granaries, the quantities of food served per day, their livestock, etc. I had become a sort of agronomist, believing that we needed statistical figures to provide proof. I drew up tables. I wasn’t really experiencing anything. My docility at the time was something I would later question!

ROUTINE OF SANDWINDS

Peasant weaving a seko lai

In every village I was offered a mud house with a straw roof, a sandy floor covered with a mat. My life was punctuated by interviews and obligatory naps in 45 degree heat. I modelled my lifestyle on that of Marc Piault, who had left for Nigeria. He behaved like a bâki [foreigner, guest] who, in these societies, received special treatment. I was housed separately, and a dish of tuo [millet paste with a black sumbala sauce] was left at my door, sometimes accompanied by a small, tough, but tasty chicken. I was alone with my storm lamp, where mayflies scorched themselves next to the books I liked to read, Marguerite Duras, Claude Simon, Nathalie Sarraute… Absolutely nothing about Africa!

My days went by in a routine fashion. The only moment of happiness was the shower when I got home. The cool water flowing over the atomic heat of the day. I took my shower behind a seko, a movable straw panel, using a bucket that the women filled every evening, just like my canari, the earthen jar into which they poured the water from the wells, which I drank from a small gourd.

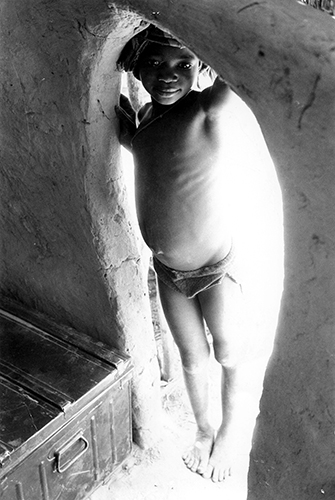

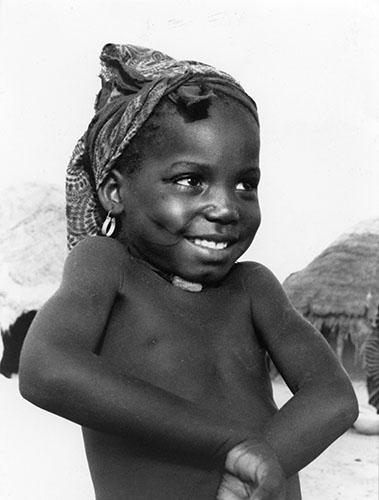

In the morning, I brushed my teeth in front of a swarm of happy, noisy little commentators who suddenly found themselves at the zoo. No matter what I did, I was stared at. But these little girls, who were freer with me because of our common gender and their very young age, played a role in socialising me. These intrepid little girls would come in and look at the things I’d brought with me, touch my hair and my skin. My language learning began with them.

Little visitors

I regretted the old-school approach to fieldwork. The previous generation co-organised the distance with what they called ‘informants’. Few made the effort to learn the language. I couldn’t speak Hausa yet, and when people from the village came to visit me in the evening, we exchanged gestures and smiles, but I couldn’t understand a word. This handicap made me feel as if I were suffocating inside and I gradually overcame it.

LEAVING

Niger was a country that seemed bleak and sad to me, and one that was also in the grip of a dictatorship. Under a reign of fear, tyranny crept into every aspect of social life like a dissolving solution that attacked any assumption of responsibility, however small.

Feeling lost, I clung to duty. I lacked passion, I respected my work, but I had no romantic attachment to ‘Africa’, with its carnivorous, over-simplified capital letters: the Africa of sharing, the Africa of philosophers, the Africa that is always laughing, the Africa of witchdoctors… I didn’t like being called ‘The African’. I didn’t like ethnologists who called themselves ‘initiates’. I didn’t like the Africanists who blithely began their talks in Parisian seminars with: At home in my village…

Devoid of any sense of belonging, I ended up preferring the hardships, tyres ripped by tree stumps, breakdowns followed by camel transport, momentary hunger, the endless silting up of sand. Luckily, I never fell ill, no doubt due to my aversion to hygiene, which must have led to a domestication of microbes. These contingencies, which Lévi-Strauss detested, led to interesting relationships, woven as they were into small dramas.

Royal guard with no horse but with his bike and radio

One day, in the sweltering heat, I heard some notes – piano bar style – coming from a nearby radio, which aroused a strong emotion. I wanted to go back to the cold, to rediscover chance, pleasure, wine and bistros, to hear the patter of my own language.

I immediately dropped all pretences and put an end to the inflexibility of a mission that I had inflicted on myself as a disorientated Jansenist. Yet, when I got back home, I was stunned by the number of objects I owned. I couldn’t understand this way of life any more. I was on my way to becoming an ethnologist.

CHANGING DIRECTION

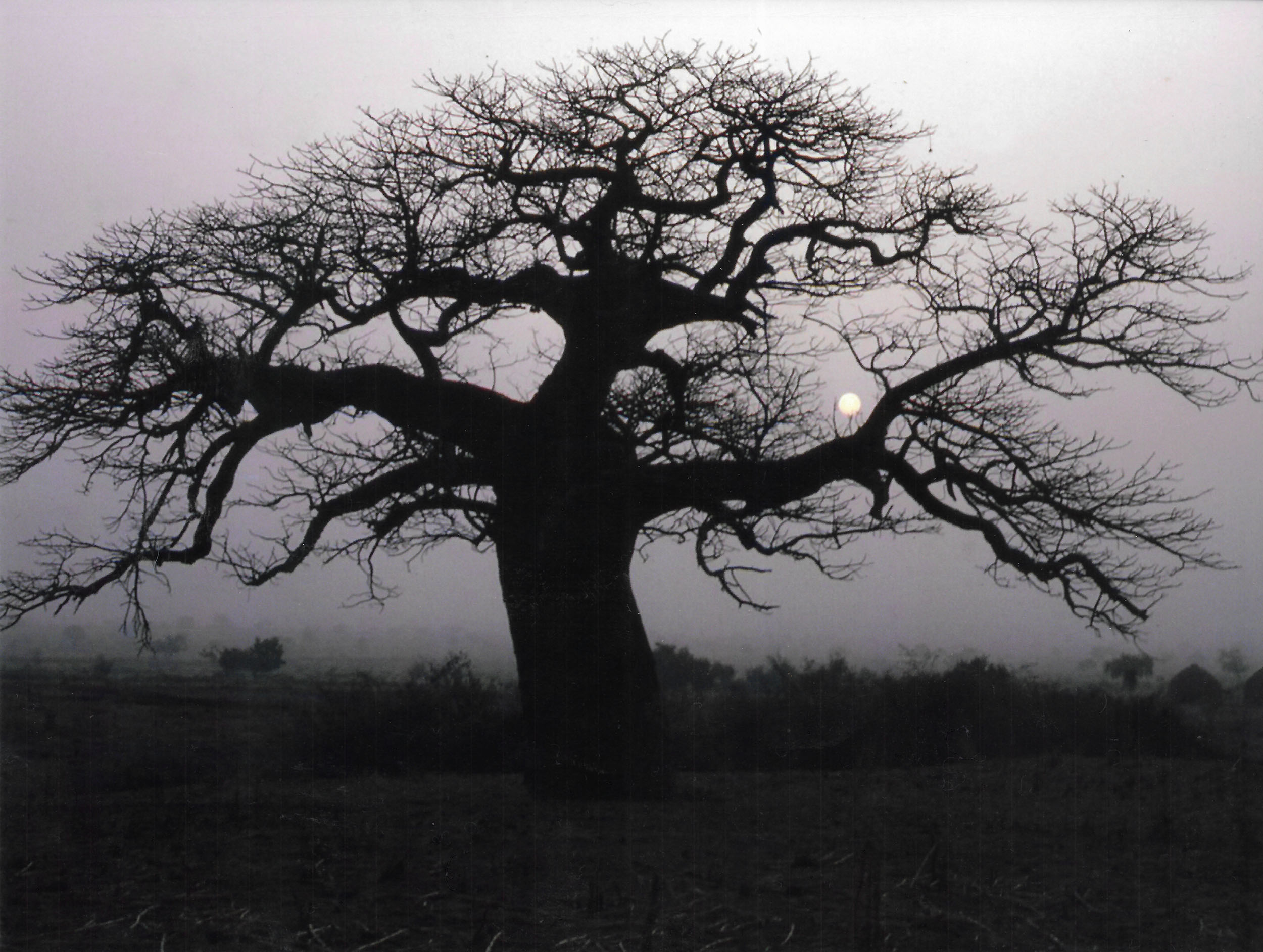

Masters of the land invoking a divinity in the trunk

I dropped the questions about seasonal ‘gap’ and irrelevant figures based on a dead end: historical facts. This land had never belonged to anyone. With colonial rules, demographic pressure and reforms to the land tenure system, ownership had been established in a lasting and conflictual way. And this is how I reoriented my thesis on these small kingdoms of the Dallol mawri hausa-speaking peoples.

The ideal time to go to these Sahelian countries is at the end of the year. That’s when Rouch preferred to be there. So did I. What’s more, it meant we didn’t have to deal with the grim Christmas break in France. On successive Christmases, we found ourselves swimming in the middle of the River Niger on the big pirogue belonging to the IRSH – the research institute – and in the evening, invariably at the same restaurant, eating kebabs washed down with half a glass of white wine and sparkling water.

Rouch organised lunches at the Centre, where among other people I met Germaine Dieterlen with her inevitable powder compact and Théodore Monod, who told risky jokes, after asking the ladies to leave the table. Unreal and extraordinary.

Jean was shooting his films in Zarma country, where I went to join him. It was a joyous, spontaneous spectacle, which I envied. The cast and crew were united by the same goal and got straight to work on the project. All I wanted to do was to drop my thesis and pick up a camera. I was leaving the standardised paths of research to face an academy that still viewed the image as Plato saw it in his cave! I had learned my trade with notebooks and index cards. I became passionate about it as soon as I could associate it with cinema.