MOVEMENT OF IDEAS

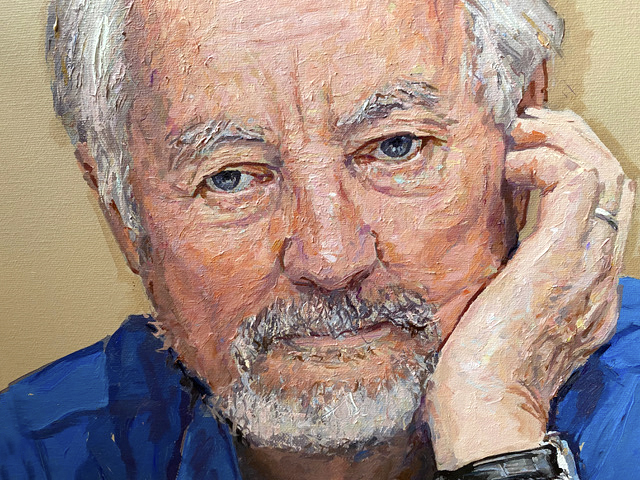

MARC AUGÉ

With doctor – Abidjan

Marc Augé began with a major work on witchcraft among the lagoon peoples of the Ivory Coast, Theory of Power and Ideology [ENS, 1975], in which he simultaneously considered meaning and power relationships, ideology and symbolic systems, actors and determinism. He highlighted the hierarchical forces in lineage societies and the logics at work through the notion of ideo-logic. He tried to link structure and history. As a good Florentine, he favoured agreements, as illustrated by his relationship with Françoise Héritier. She was an epigone of Lévi Strauss at the Collège de France; he was an heir to Balandier and President of the École de Hautes Etudes.

Powers of Life, Powers of Death [Flammarion, 1977].

The Genius of Paganism [Gallimard, 1982].

THE CONTEMPORARY

For Marc, if anthropology continued to cling to lost traditions, to the last surviving groups, to languages spoken by fifty people… it would become a learned science, like Romance philology for example, disconnected from the world and probably from general and national education. This is how he came to contribute to the book Le Sauvage à la mode [cf. Le Sauvage à la mode].

In the 1980s, he launched a new research theme: illness as a “social fact” [Le Sens du mal : anthropologie, histoire, sociologie de la maladie [EAC,1984]. At the same time, he was attracted by the modernity of everyday life and global movements, without ever abandoning his master concepts of otherness, identity and plurality.

He made the “anthropology of the near” and “supermodernity” his field of predilection, of which Non-Places (1992) became a standard: globalisation flattens time and space in favour of extreme individualisation that “standardises and prevents otherness”. In 1993, he published his manifesto book, Pour une Anthropologie des mondes contemporains, and in 1996 set up his eponymous research centre at the EHESS.

As a ‘post-modernist’, Marc has nevertheless remained very attached to the contribution of the Enlightenment, and has never questioned the universalism of relation to cultures, or science insofar as it accumulates knowledge and critical examination.

GOING OUT

As I mentioned earlier, I attended Marc’s seminars at EHESS, on rue de Tournon and then rue de La Tour, in tandem with Jean Bazin. It was there that he forged fluid friendships between his private and professional lives. I also attended Jean Rouch’s Saturday morning classes at Chaillot. This consisted of watching films of improbable shapes. These playful, sensitive spaces were open to debate, and to the many parties with their versatile geography love lands.

FREE ESSAYS

Very early on, Marc emphasised the notion of the ‘author’: the ethnologist is not simply a vector of cultures, but interprets and shapes knowledge in order to pass it on. With his desire for modernity, he willingly abandoned the scientific credos and the great academic machines to work on the contemporary through free and experimental essays, documentary or fictional films and novels.

“Science has the good fortune and modesty to know that it is in a state of provisionality, able to shift the frontiers of the unknown and move forward”, he said [2001].

He legitimised my enthusiasm for cinema and my pleasure in working in a wide variety of fields: a reconciliation between theory and film that unleashed my passion for ethnology. He reassured and encouraged a number of young researchers with his capacity for happiness in the search for Carpe diem.