MALIK AMBAR

Historical novel

An African slave, initially an outcast due to servitude, went on to become a Regent King in 16th and 17th century India. This African hero in a foreign land succeeded in not only protecting but also extending the Kingdom of the Deccan. His extraordinary fate is inextricably linked to his encounters with a range of exceptional characters.

AN ENCOUNTER

A change of gears

Janjira Fort where Malik went to obtain mercenaries for his last great battle.

One day, by chance, I happened across a few lines on the Internet describing Malik Ambar’s life. Originally a slave from Abyssinia, he had embarked on an extraordinary journey of emancipation and gone on to hold the highest of political positions in India, and yet his legacy had remained in the shadows because he was black.

In his lifetime, Ambar was praised as a great statesman. The vestiges of the city he founded still stand today in his former Kingdom of Ahmednagar, where other memories also live on: his military innovations, his prescient water technology, his progressive stance towards minorities (from which he himself hailed), and his religious tolerance, despite his own attachment to Islam.

I had stumbled across an Abyssinian saviour whose story broke with every possible preconception about helpless Africans!

What a wonderful opportunity to counter the racist views framing Black people as never fully actors in their own history, only ever a negative presence in the history of others. We know all about their suffering, but what of their contributions to the world? This injustice prompted me to look further, to dig deeper, and, ultimately, to write.

I began this historical inquiry with a view to making a film. I used fiction to bridge the gap between the figure forged by Indian historians in the 1950s-1970s – that of an infallible and pious warrior – and Malik Ambar, the man himself.

A script saw the light of day but it was too costly for producers and thus became a novel instead.

« Men, whether young or old, need stars to build their self-esteem.

But no one ever told me about Black stars »

Lilian Thuram

Released on 3 Mai 2011 by Éditions Steinkis

Preface by Jean-Christophe Rufin

15x23cm – 296 pages

« A successful experiment. This is a real novel playing an appealing narrative game that draws in the reader just as it seems to have drawn in the author »

Jacques Revel, historian. Director of studies of the EHESS

« Malik Ambar is a visionary saga. And a beautiful novel »

Jean-Christophe Rufin, Académie française

« Malik Ambar is a true gem, an epic that is constantly nourished from this little known part of history. An anthropologist by trade, with the meticulous precision of the researcher and blessed with a storyteller’s imagination and an undeniable talent for writing, Eliane de Latour presents us with a very unusual historical novel in the epic tale of Malik Ambar. With the exception of a few scholars, passionate about the history of the Indian subcontinent, Malik Ambar is completely new ground for most of us.»

Monique Zetlaoui – Littératures Sud

“The author uses her imagination to give flesh and blood to this story, which is not just symbolic of African presence in the medieval world. It is also the tale of a mixing and intertwining of worlds that was unprecedented of its time..»

Tirthankar Chanda – RFI

File to download

THE STORY

Of Malik

As a teenager, an Abyssinian slave was bought by Wazir Changez Khan, the Prime Minister of the Kingdom of Ahmednagar in Deccan.

When he became a free man, taking on the name Malik Ambar, the Abyssinian discovered the gardens and poetry paradises foretold in Persian cultures.

He also developed a strong sense of justice, thanks to his loved ones, and committed himself to protecting the kingdom that had given him his dignity back.

The story is told in the synopsis.

A STORY

Of emancipated slaves

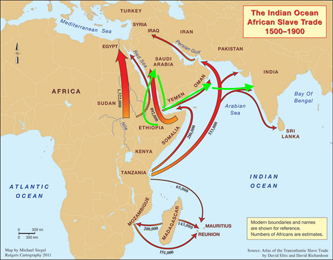

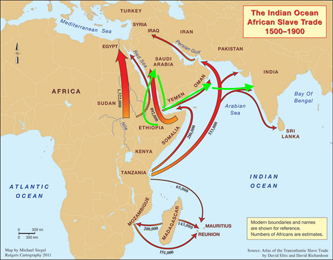

Centuries of evidence testify to contacts between Africa and India. Certain historians go as far back as Antiquity, but it is in the 12th and 13th centuries that connections developed the most. Long before the triangular trade of the Atlantic, dynamic slave-trade routes existed between India and the Dark Continent, also transporting tradesmen and political representatives.

Arab sailors dominated the Indian Ocean at the time. They scoured the eastern coasts of the Dark Continent going on to sell their human merchandise first on the Arabian Peninsula and then in Gujarat and on the Malabar Coast.

Unlike the ‘domestic slaves’ known as Siddis, the Habshis, captured in Abyssinia [Ethiopia], were expensive luxury slaves, purportedly endowed with exceptional qualities of bravery, loyalty, and intelligence.

‘All the nobility were mad about them. In a sense, the Habshis were the aristocracy of the enslaved’ explains the Venetian tradesman in my novel.

Dynaste d’origine africaine,

©Kenneth X. Robbins, John McLeod. Ed Mapin, 2006

The emancipated Habshis became Prime ministers, army leaders, and ministers of justice; when they received a fiefdom as a tribute, they went on to found new dynasties; and they reached supreme office via the Regency. The destinies of these talented Africans were, however, obfuscated by the British and Indians alike.

Today, though, certain historical studies on India are redressing the balance in terms of the huge sections of the country’s history that have remained invisible, as John McLeod has pointed out. McLeod is at the head of a group of researchers in the United States eschewing both Euro-centric and African-centric perspectives. They aim, instead, to highlight the political, military, and cultural roles played by Africans in Southern Asia, thereby encouraging readers to revisit their preconceptions on the matter.

The consensus is unanimous, Malik Ambar was the most important and most emblematic of these high-ranking figures from the African slave trade. Plundered by Arabs in Ethiopia, the young man was sold in Mecca where he earned the protection of a tradesman, no doubt won over by his intelligence. The extent of this protection was such that, upon the tradesman’s death, his jealous children sold Ambar on to a slave trader leaving for India.

As Richard Pankhurst has also pointed out, while a considerable body of literature exists on the Atlantic African diaspora, the African diaspora in the Indian Ocean remains woefully understudied.

A STORY

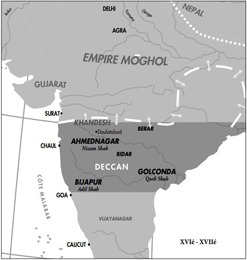

About the Deccan

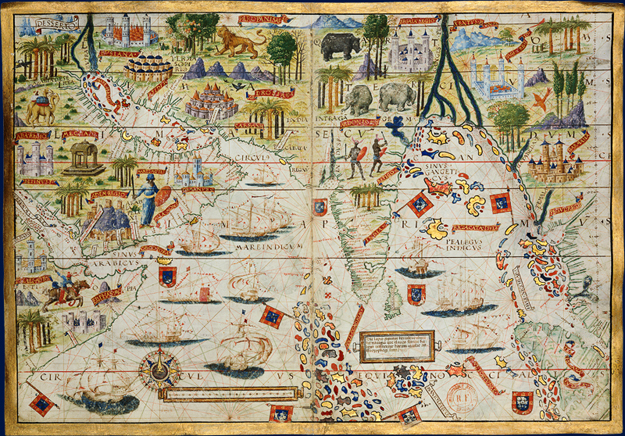

Miller Atlas Early 16th C Portuguese cartography

© CNRS-BnF, 2019

Fluctuating borders.

Green > Plausible routes for Ambar’s enslavement

©Web-Carte

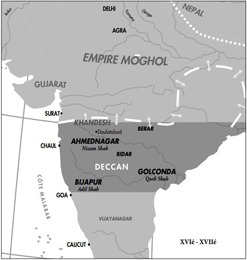

In the 16th century, the Mughals crossed the Indus from the Samarkand as victorious invaders, settling in the north of the country. Abkar the Great, grandson of the founder of this new dynasty of Persian culture, continued the conquest begun by his ancestors aimed at subjugating and unifying Hindustan under the imperial crown.

However, he encountered an obstacle in the shape of continued resistance from the Deccan Sultanates of Turkish-Afghan origin, established in the region since the 13th-14th centuries.

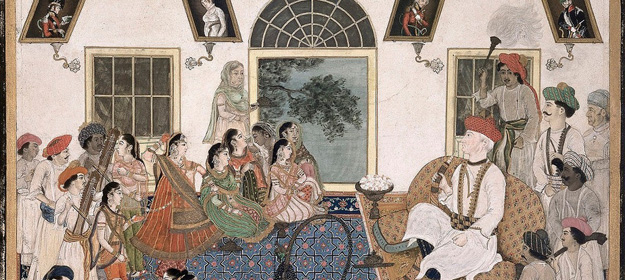

In the royal courts of this central region, Uzbeks, Turks, Arabs, Persians, Afghans, Africans, and Tajiks rubbed shoulders, alongside the native Hindu Marathi who would play their hand a little later in the game.

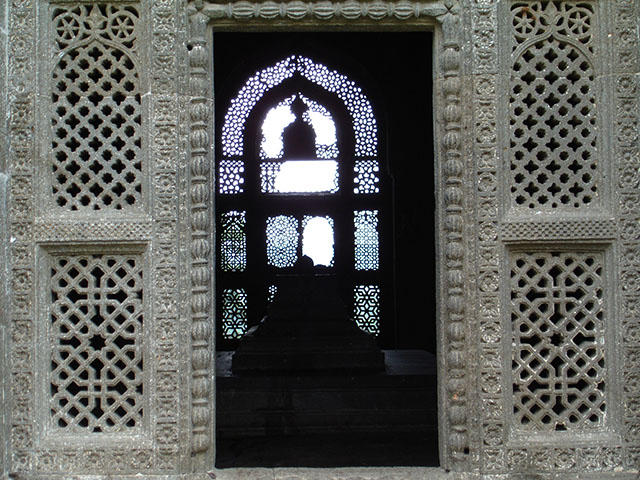

Inside

This melting pot was not to everyone’s taste, however, and particularly not the nobility who claimed to have their roots in the noble ancestry of the North. They coalesced in the Foreign Party, the Afaqis, defining political rule as their exclusive preserve and declaring that by virtue of ‘nature’ they and they alone were apt to rule, the defining feature of this natural election being their light skin. Standing in opposition to this party were the Deccan Muslims, a diverse and mixed group brought together by a form of ‘patriotism’ based on their land, their tombs, and their freedom, much like the historical characters in the novel.

This explosive context led to infighting among Muslims who also found themselves battling the imperial Muslims of the North. Westerners lost no time in taking advantage of the situation.

In this context, Malik Ambar’s political adventure had crucial stakes, reaching beyond the narrow interests of the royal princes who, in the absence of birthright, were killing one another left, right, and centre. In order to achieve political peace, society itself had to become more stable by overcoming the cultural divides of knowledge and religion.

The Great Mughal Akbar, in power when the Abyssinian slave began his political rise, was firmly convinced of this.

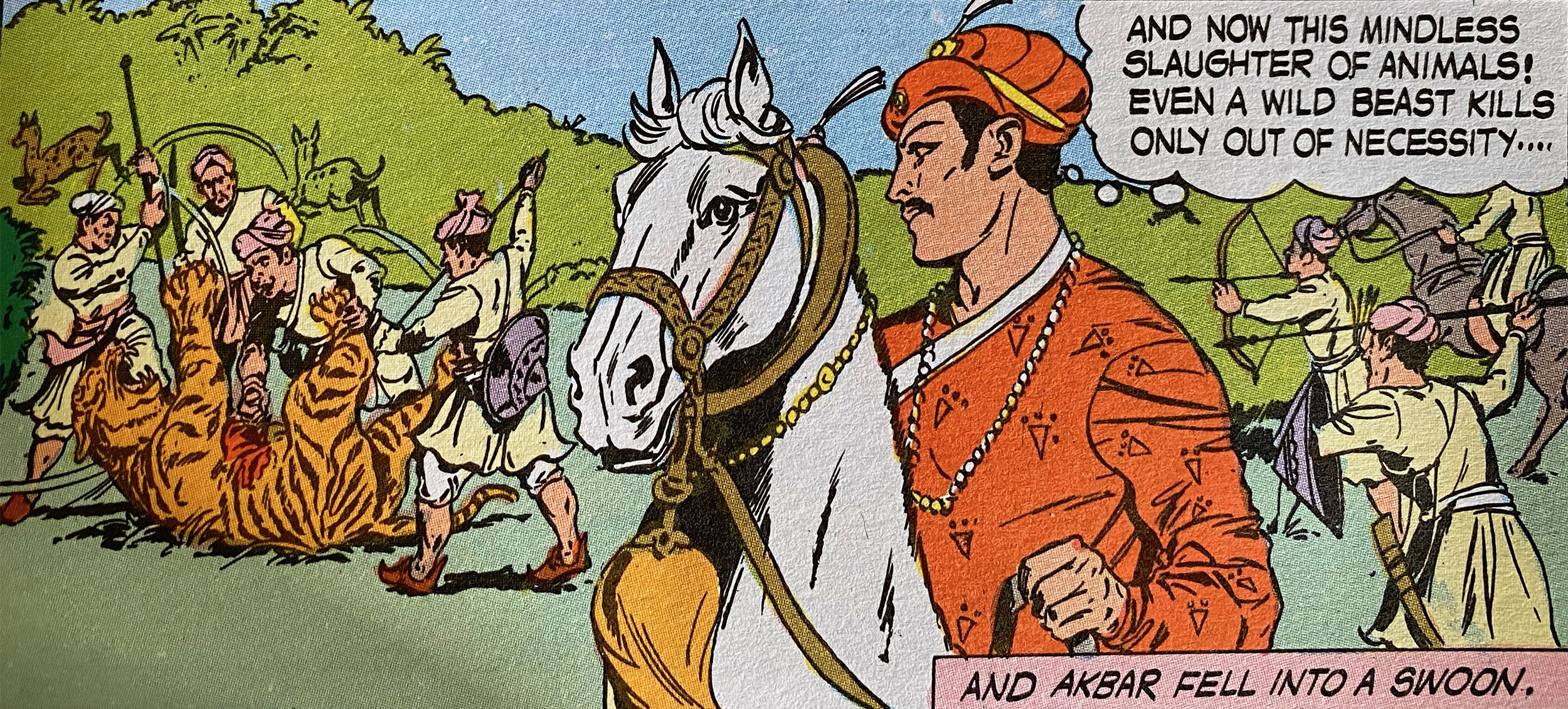

When he found time between massacres, the Emperor – who was illiterate and largely agnostic – was fascinated by metaphysical debates. He created an increasing number of Houses of Knowledge bringing together philosophers and poets.

He unified the calendars of Islam and Hinduism so that everyone celebrated festivities at the same time. He prohibited the more divisive or discriminatory traditions such as Sati or the marriage of young children. A Muslim himself, he married a woman from a Hindu minority, the mother of the future Emperor Jahangir.

He was at once Malik Ambar’s enemy and his inspiration. Like him, Ambar was an opportunist, moving his pawns according to the strategy most likely to serve the general interest, even when this came at the price of dishonest compromise. Or else he chose merciless war, which did not prevent him, unlike his model, from finding a source of inner equilibrium in prayer, practised in the street alongside the poor

Great Mughal Akbar.

Outside

The Portuguese arrived in Calicut in 1500. A century later, the English, under the banner ‘Trade not Territory’ were progressively establishing the East India Company. Neither the Dutch, focused on Insulindia, nor the French, who arrived later, were faced with the black hero.

In the novel, while the Portuguese in Goa play an important role in the early stages of the story they are then relegated to the background, whereas historically they remained present. I chose instead to place the English centre stage, focusing on their first steps in India in the presence of Malik Ambar, who could sense that these Westerners were driven by the lure of gain.

Popular comic book excerpts

©RdAnant Pai-PG.Sigur-n°603-Rs30

Poster chromo of Shivaji.

A STORY

Of subaltern nobility

Fluctuating borders.

Green > Plausible routes for Ambar’s enslavement

©Web-Carte

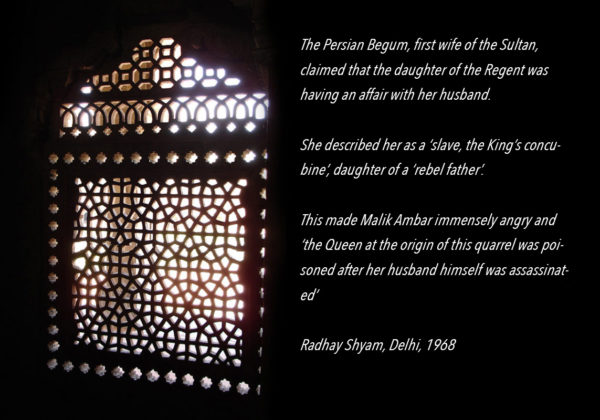

Women, seen as matrimonial livestock, consolidated political alliances. History makes no mention of them. This is even true of the Princesses, the Persian begums, and the ladies of the court, let alone the governesses, servants, or, worse still, the slaves in their service.

Only a few exceptions such as Chand Bibi have found a place an academic history. This queen is known in India for her beauty, her great erudition, and her courage in battle against the powerful Mughals.

METHOD

A documentary fiction

This fictionalised tale of Malik Ambar’s life is based on real events and unfolds against a historically accurate social and political backdrop. However, it was impossible to piece together the exact chronology of the Kingdoms of Deccan. A range of dates relating to marriages, wars, and peace treaties only served to confuse the issue, a situation little improved by the tangle of facts that differed depending on the author. An antiquated historiography dominated Indian academia in the 1960s and 1970s.

Ancient Persian sources were linguistically inaccessible to me and with only secondary material at my disposal it was unrealistic to think I could judge one version of events compared to another. In these conditions, writing a biography was impossible. Moreover, given the dry historical material available about Ambar – either glorified when the focus was on Ancient Deccan or obfuscated in general history – it would have proved an arduous task to say the least. A more intuitive approach seemed necessary.

Traces of time

As soon as I was able, I turned to oral history as I had often done in Africa in the past.

The figure of Malik Ambar is still present in certain villages, particularly around Ahmednagar where his legend lives on.

It has been passed down orally, with the usual embellishments that come with edifying narratives; it lives on in a few manuscripts preserved and recounted by local scholars; it is present in the work of amateur historians who devote their lives to the genealogies and events of their local region.

Armed with this historical ethnography, I went to the Deccan Library and the Puna Historical Centre where I conducted archival research, aided by a dark-skinned elderly clerk who brought me documents by the cart-load and guided me in my quest with ineffable sagacity.

Eminent authors such as historian Sanjay Subrahmanyam or novelist Amitav Gosh, among others, opened my eyes to the transcontinental movements that went hand-in-hand with Western discoveries and conquests.

Jafer Bhei Ambari, one of Ambar’s descendants.

Hamrapur.

Mirza Beg, scholar from Aurangabad.

Traces of reality

« The Old Fort of Ahmednagar where the elite of the Kingdom congregated around Sultana Chand Bibi.»

Catholiques – Procession de Pâques à Goa.

Islam shite. Procession de l’Ashura (Muharram), Mumbay.

Islam soufi. Mosquée de Hamrapur et temple hindou derrière.

Hindousime. Entrée d’un temple.

« If a Mosque emerges, a Church will be built beside a Hindu temple »

Hamrapur.

Khuldabad.

« Hamrapur Mosque where he made a fatal stop and received the first funeral rites.

His tomb is still honoured there by a Sufi brotherhood »

METHOD

A fictionalised document

By condensing time, I tried to summarise the main symbolic phases of this hero’s life: emancipated slave, desperado, statesman, compromised leader, and, ultimately, rebel. Each stage brought its own love stories and bereavements, the wellsprings of a rebirth following servitude.

Malik Ambar’s exceptional destiny could seem self-evident as part of an epic tale of masculine glory – or so History would have it, at least. And yet only fortuitous encounters with a range of exceptional characters can truly explain how a slave in a foreign land rose to such a powerful political position.

In the novel, I brought three members of different generations of Indian nobility onto centre stage. The Begum, wife of the Sultan of Ahmednagar and mother of Chand Bibi [Ambar’s secret mistress] who gave birth to Sharba. Three female characters, purveyors of the spiritual and the carnal. I construed and fictionalised all three by drawing on minor episodes related by historians.

Once I had brought Sherba onto the stage, I tied her to a fictional character named William – a young English officer. This built a bridge with the new conquerors – not the most well-known, from the next stages of colonial history, but the first of the English to arrive on the continent either as tradesman or drafted by the East India Company.

Fascinated by India and Eastern lifestyles and thinking, many young English men donned the robes and espoused the customs of their hosts. Sometimes they fell desperately in love with a silhouette wrapped in a voluptuous sari, a far cry from the corseted bustiers and starched skirts of the young English girls taken out of their convents and sent by the boatload to India to try and bring the Crown’s representatives ‘back to reason’.

William Dalrymple based his magnificent novel, White Mughals, on the confrontation between these two civilisations, which he examines through the eyes of a hero named James Achilles Kirkpatrick, madly in love with a young Begum. This tale allowed me see these initial contacts from another angle and inspired me in my own endeavour, despite the fact I was focusing on a slightly early period.

The White mughals © William Dalrymple, 2002.

PRESS

Excerpts

FRANCE CULTURE – A PLUS D’UN TITRE

Tewfik Hakem s’entretient avec Eliane de Latour de son roman Malik Ambar.