THE “CASA DES GO”

An “anti” humanitarian social project

The Go are among the most vulnerable groups but suffer a very specific form of stigma as they are morally disgraced in a way that relegates them beyond poverty itself. Excluded from society, they are perceived as depraved children who have brought dishonour upon themselves, as profaned mothers, as dangerous urban nomads.

Their very existence testifies to the oppression of young girls worldwide, particularly when it isn’t considered necessary to send them to school. Too young and too wild, they find themselves pushed into the blind spot of a society that rejects everything it does not need. On all five continents, new pariahs are springing up in these marginal spaces.

By agreeing to step outside their clandestine lives, these girls from Abidjan shed light on the lives of all those who remain hidden in the blind spot of the world.

LOOKING AHEAD

Escaping stigma

Thanks to the first photo exhibition “Go de nuit. Les belles oubliées” shown at the “Maison des Métallos” in 2011, these young women’s status as victims was finally recognised, whereas in their own society they were held responsible for their fates because they sold their bodies to survive. Racked by shame, they had chosen to hide in the shadows of clandestine life. When their portraits were exhibited, they understood that they could act upon their own destiny: the exhibition raised 10 000€ which was used to fund a social project that we called the “Casa des Go”.

I pursued my work as an ethnologist, photographer and film-maker as part of my engagement in this project. A new window into their lives opened up for me.

Cours de théâtre psy à la Casa

When I came back to Abidjan having kept my promise, my first step was to try and find an NGO. But I encountered only setbacks and disillusionment. The local administration perceived the ghetto Go girls as a nuisance, who had no hope for societal rehabilitation and who would be a heavy burden not only for their workload but also for their results, measured in terms of quantities of people ‘saved’, medication administered, material provided, etc.

In the end, I ran the project myself, with 10 girls and the support of both the Amigo Doumé Foundation and a few individuals from outside. We rented a flat located next to a state Social Centre as I thought their support might also prove useful. However, the teachers had trouble accepting the Go’s outlandish behaviour and the activities were unsuccessful, with very un-educational timing – it is hard to teach punctuality, when one is an hour late oneself! After a while, the flat became the girls’ only referential framework. It closed after 7 months, during which its inhabitants had enjoyed a level of protection that had previously seemed unthinkable given their chequered pasts.

The ONUCI, through the Human Rights Commission, had unanimously approved this project and agreed to support its second phase, after the first three months of stabilisation I had initiate. The money arrived a year late and was taken by the neighbouring Social Centre, which had been involved at the beginning.

La casa 1

La casa 2

TAKING ACTION

Gender norms

A range of activities were organised to help the girls make the most of their individual talents and personal experiences including literacy classes, sewing classes, jewellery-making, selling cooked meals, educational trips, and so on. However, the girls’ journey of personal discovery remained limited by the unconscious intergenerational reproduction of fixed gender norms.

The girls lived in fear of what others might say or think and of the rumours that could circulate and potentially devastate them in a society so clearly built on appearances. They were easily thrown off balance by the judgments of outsiders.

It was difficult for the Go to escape gender norms when it came to choosing a trade. As the song “Série C” says, they all imagine going on to work in Cooking, Clothing, Cleaning, Coiffure.

And yet why could a woman not be a painter, a builder, a gardener, a carpenter or a mechanic? The Go in the Casa answered this question with an aporia: because they’re men’s jobs.

RESPECTING DIGNITY

Running counter to international humanitarian work

Running counter to the humanitarian protocols determined in high places, we chose instead to create a small-scale project that adapted its provision to the young girls rather than the reverse. International aid seems to provide solutions that reduce human beings to stomachs to fill and bodies to house. ‘The poor will buy themselves some ‘small luxury’ first before feeding themselves’ [Duflot, 2011]

Like the I.B.C.R [International Bureau for Children’s Rights] dealing with rehabilitating former child soldiers, we rejected the ‘existence of a typical pattern’ [Le Monde, 12-02-2012] as entirely inapplicable to those who find themselves in violent environments at such a young age: increasingly, these girls encounter their first client around the age of 9, 10.

At the international conferences where major social strategies are decided, different definitions of aid tend to both align and enter into competition. ‘Care’ policies are often grounded on marketing principles more than on analysis or documented fact. The Go girls from the ghetto fall by the wayside when it comes to the main classifications or are subsumed within categories in which they become invisible. Their specific behaviour only serves to accentuate this exclusion.

Vendeuse d’eau. 0,0076 € le sachet

ACHIEVING REHABILITATION

Activities in the casa

Today, the main international bodies are progressively starting to recognise the 10- to 24-year-old women left by the wayside across the world, 600 millions accrording to a study quoted by Le Monde [17-04-2011]. This age group, both universal and specific to unprotected environments, remains woefully inexistent in the social breakdown of timeframes. At best, it falls under the very loose term of ‘youth’ which obviously also extends semantically to young men.

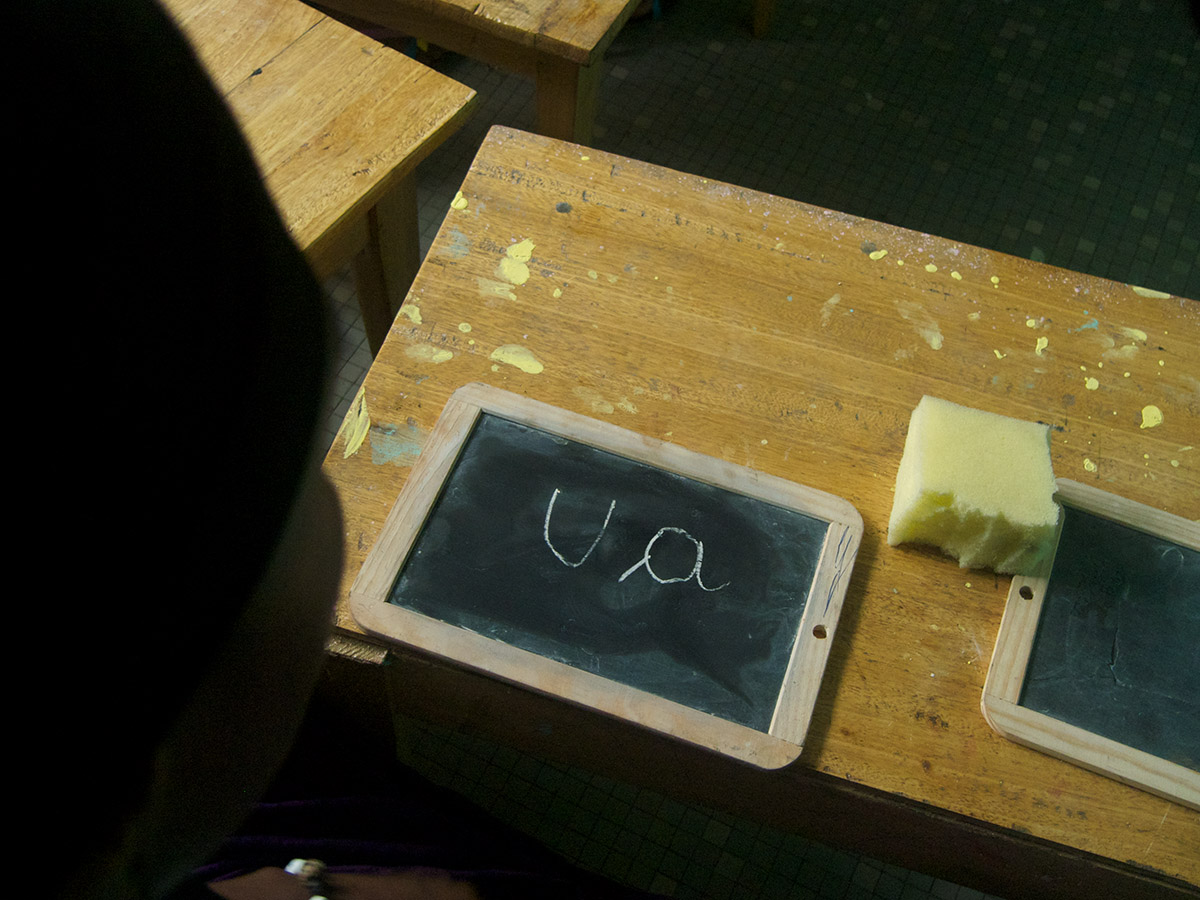

Literacy

The girls had lessons every morning. Their teacher Roger helped them prepare them for a competitive exam organised by the World Bank, which provides access to jobs. The girls had to reach the equivalent of Year 3/Grade 2. They all failed, except Melissa who reached the equivalent of year 10/grade 9.

Identity papers

It was of the utmost importance to get birth certificates and identity cards for these girls, considered as ‘nobodies’. Papers would give them access to citizenship, allow them to open banks accounts and both save their money and keep it safe.

Family mediation

They were reticent to face the judgment of their families, who often rejected them. They believed they had caused great harm to their loved ones, who held them responsible for all their misfortunes – illness, job losses, and deaths. When this mediation resulted in approval and put words on everything previously left unsaid, an enormous weight was lifted off the girls’ shoulders. However, as the photos show, forgiveness did not always work its magic and then the girls had to start again.

Medical issues

Their bodies escaped them. Hollow shells, which they decorated with masks of beauty but of which they took no care. Once in the Casa, competition among the girls around health care sometimes led them to seek attention for imaginary illnesses. But they are in a bad health and, among others, we did discover one case of HIV, which made the girl in question aware of her illness.

Educated choices

We tried to show them other jobs and discuss visits to various companies with them: rabbit breeding, farming, carpentry, ironwork, gardening. Nothing promising came of this.

MOVING FORWARD

The Casa Go Girls

La pauvreté comme horizon unique. Les go de ghetto voient là un repoussoir qui guide leur être tout entier pour que plus rien, même pas un signe, ne rappelle le dénuement dans le futur.

Des vocations diverses et fragiles ont émergé de la Casa. En février 2014 date sa fermeture, sur dix filles, quatre sont devenues autonomes. Elles ont rejoint des écoles professionnelles à côté desquelles nous les avons logées, sauf une qui a choisi une boutique près de sa cour familiale.

Femme grattant des sacs de ciment

With poverty as their only horizon, the Go from the ghetto saw it as something to avoid at all costs and that informed everything they did to try and make sure nothing in their lives ever resembled destitution again, not even a scarf or a pair of earrings that could refer back to it.

In the Casa, various fragile vocations emerged. When it closed in February 2014, four of the ten girls were now autonomous. Three had enrolled in professional schools and we had housed them nearby, while the fourth had chosen to build a shop near her family’s courtyard.

Safi is clearly the project’s greatest success story. After some ups and downs, she agreed to leave Abidjan for Grand Bassam, 30 km away, where we linked her up with an Italian NGO called Abel that gave her a professional framework while I paid the rent on her house. Today, she makes her own jewellery that she sells on the beach.

The film ‘Little Go girls’ won a prize worth 1500€ at the Verona Film Festival. I gave a large part of this to Safi so that she could build a shop with the help of Abel and gave the rest to the others.